They have a healthy disrespect for respectability; they are not ashamed of being agitators and trouble-makers; they see it as the essence of democracy

wrote Howard Zinn about the young black activists fighting segregation[1] – “whose sacrifice [was] tossed, anonymously, into the common pool”, and who understood that

Revolutionary change does not come as one cataclysmic moment (beware of such moments!) but as an endless succession of surprises, moving zigzag toward a more decent society. We don’t have to engage in grand, heroic actions to participate in the process of change. Small acts, when multiplied by millions of people, can transform the world.[2]

It was they who were of primary interest to Howard Zinn, the historian, the people’s historian – whose A People’s History of the United States “literally changed the consciousness and the conscience of an entire generation,” according to Noam Chomsky.

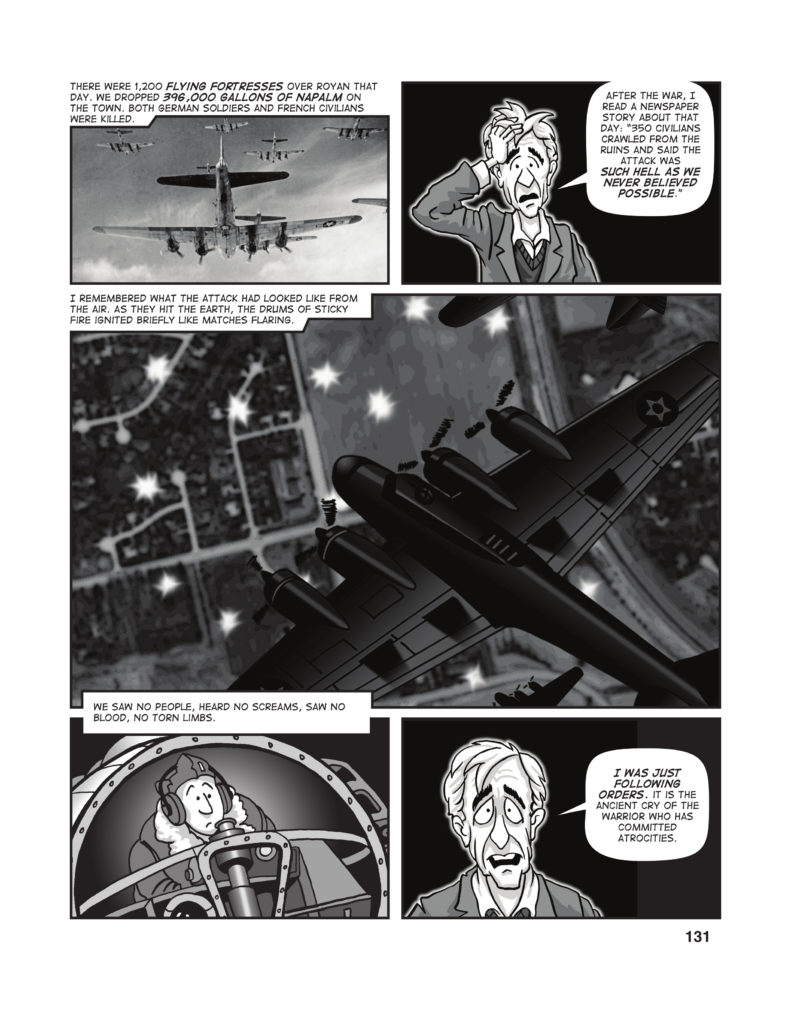

Zinn (1922–2010) served as a bombardier in the United States Army Air Corps during the Second World War. This war – as the “just war” against fascism – has served as a justification to other wars ever since. His experience has, however, turned Zinn into a life-long anti-war activist. In his recollections, he identifies as a defining moment the April 1945 US bombing of the French town of Royan, where several thousand German soldiers had taken shelter: [3]

When US president George W. Bush declared the “war on terrorism” in 2001, Zinn asked, “How can you have a war on terrorism when war itself is terrorism?” War on terrorism, he emphasized, “gives the government a perpetual war and a perpetual atmosphere of repression. And it generates perpetual profits for corporations. But it’s going to make the world a far more unstable and dangerous place.”[4]

“We shall make no distinction,” the president proclaimed, “between terrorists and countries that harbor terrorists.” So now we are bombing Afghanistan and inevitably killing innocent people because it is in the nature of bombing (and I say this as a former Air Force bombardier) to be indiscriminate, to “make no distinction.”[…]

They have learned nothing, absolutely nothing, from the history of the twentieth century, from a hundred years of retaliation, vengeance, war, a hundred years of terrorism and counterterrorism, of violence met with violence in an unending cycle of stupidity. […]

We are committing terrorism in order to “send a message” to terrorists.[5]

After the end of the Second World War, Zinn went to study history at New York University:

I started studying history with one view in mind: to look for answers to the issues and problems I saw in the world about me… Sure, there’s a certain interest in inspecting the past, and it can be fun, sort of like a detective story. I can make an argument for knowledge for its own sake as something that can add to your life. But while that’s good, it is small in relation to the very large objective of trying to understand and do something about the issues that face us in the world today.[6]

In traditional curricula,

[t]he people it was considered important to study were presidents, industrialists, military heroes – not labor leaders, radicals, socialists, anarchists.[7]

And Zinn was much more interested in the latter than in mainstream historical figures. As he stresses in his book on democratic education:

So often the history of war is dominated by the story of battles, and this is a way of diverting attention from the political factors behind a war. It’s possible to concentrate upon the battles of the Mexican War and to talk just about the triumphant march into Mexico City and not about the relationship of the Mexican War to slavery and to the acquisition of territories that might possibly be slave territories.

Another thing that is neglected in the history of the Mexican War is the viewpoint of the ordinary soldiers. […] I think it’s a good idea also to do something that isn’t done anywhere so far as I know in histories in any country, and that is: tell the story of the war from the standpoint of the other side, of “the enemy.”[8]

It was also clear to Zinn that the neutrality of historiography and historians, proclaimed by many be an unquestionable ideal, was an illusion that would fail at the very choice of subject.

…there is no point even trying to be neutral, because you can’t. When I say you can’t be neutral on a moving train, it means the world is already moving in certain directions. Children are going hungry, wars are taking place. In a situation like that, to be neutral or to try to be neutral, to stand aside, not to take a stand, not to participate, is to collaborate with whatever is going on, to allow that to happen. I never wanted to be a collaborator, I wanted always to intercede into this moving world and see if I could deflect it by even the slightest of degrees.

We all face that problem. We all go into professions where you’re supposed to be professional. And to be professional means that you don’t step outside of your profession. If you’re an artist, you don’t take a stand on political issues. If you’re a professor, you don’t give your opinions in the classroom. If you’re a newspaperman, you pretend to be objective in presenting the news. But, of course, it’s all false. You cannot be neutral. If you’re a historian and you’ve been brought up to believe that you’re objective as a historian, you’re not taking a stand, you’re just presenting the facts as they are, you’re deceiving yourself, because all the history that’s presented in books or in lectures and so on is a history that’s selected out of an enormous mass of data. When you make that selection, you’ve decided what you think is important. That comes out of your point of view. So, one, it’s impossible to be so-called objective and neutral. Two, it’s not desirable, because we need everybody’s energy, we need everybody’s intervention in whatever’s going on.[9]

As a history teacher, he did not separate his teaching and activist roles – and encouraged his students to become involved in activism, too. From 1954 to 1963 (when he was fired for insubordination), he was a professor of history at Spelman College, a “black college” for women in Atlanta, Georgia.

I was open to anything my students wanted to do, refusing to accept the idea that a teacher should confine his teaching to the classroom when so much was at stake outside it.[10]

His students – with Zinn’s support – challenged the segregation rules of the city’s public libraries, and through persistent action, had them abolished.

With his teaching methods, Zinn sought to counter what he described in his book on democratic education:

[W]hile schools are charged with promoting a discourse of democracy, they often put structures in place that undermine the substantive democratic principles they claim to teach. As a result, schools are necessarily engaged in a pedagogy of lies.[11]

Both in the action of the Spelman students and in general, he considered civil disobedience, the deliberate violation of unjust laws to be key elements of democracy. As he put it in his book Disobedience and Democracy – Nine Fallacies on Law and Order,

There is no social value to a general obedience to the law, any more than there is value to a general disobedience to the law. Obedience to bad laws as a way of inculcating some abstract subservience to “the rule of law” can only encourage the already strong tendencies of citizens to bow to the power of authority, to desist from challenging the status quo. To exalt the rule of law as an absolute is the mark of totalitarianism, and it is possible to have an atmosphere of totalitarianism in a society which has many of the attributes of democracy. To urge the right of citizens to disobey unjust laws, and the duty of citizens to disobey dangerous laws, is of the very essence of democracy, which assumes that government and its laws are not sacred, but are instruments, serving certain ends: life, liberty, happiness. The instruments are dispensable. The ends are not.[12]

He repeatedly emphasized the importance of challenging the state:

Perhaps the most important thing I learned was about democracy, that democracy is not our government, our constitution, our legal structure. Too often, they are enemies of democracy.[13]

When a government betrays those democratic principles, it is being unpatriotic. A love of democracy would then require opposing your government. It would require being “out of order.”[14]

When the great journalist I.F. Stonewas asked by journalism students for advice, he had two words: “Governments lie.”[15]

And he did not only speak about the necessity of challenging the authority of state, but he also acted.

Working at RAND Corporation, his friend Daniel Ellsberg had access to confidential military documents about the Vietnam War – which provided a clear proof of I.F. Stone’s comment. With some colleagues, Ellsberg decided to copy the documents and publish them in the press. Ellsberg left a copy with Zinn, who stashed it in his office.

For once, the mainstream press – which is usually aligned with the US government’s war narrative – took up the conflict with the government, and The New York Times published the Pentagon Papers in June 1971.[16] Ellsberg went into hiding for a few days and then, accompanied by friends, supporters and journalists, turned himself in to the police. He risked 115 years in prison under the Espionage Act – today Julian Assange could face 175 years in prison on similar charges. The charges against Ellsberg were soon dropped. The scandal of the Pentagon Papers hastened the end of the war.

Zinn’s deep opposition to war and strong reservations about state power – as well as his activism rooted in direct action – logically turned him to anarchism.

What also connected the movements of the 1960s to the historic philosophy of anarchism was the idea of direct action. This meant that social change would not be sought by political parties striving to take over government, but by citizens banding together and acting directly against the source of their oppression…

It was in the late 1960s that I began using anarchist writings in my course in political theory at Boston University. My students were reading Emma [Goldman]’s autobiography, Living My Life, as well as a collection of her lectures, Anarchism and Other Essays. Sometimes I used a short book by Alexander Berkman, which was a concise and simple explanation of anarchist ideas, called The ABC of Anarchism. I began teaching a seminar, “Marxism and Anarchism.”[17]

Zinn’s anti-war activities as a lecturer led to confrontations with the university president, John Silber. One of Silber’s first acts after his appointment in 1972 was to invite the Marines to the university to recruit among students. A protest against this was broken up by police force. The next day, the official newspaper of the university administration carried the headline “Disruptive Students Must Be Taught Respect for Law, Says Dr. Silber”. Zinn published his response in a Boston newspaper:

“It is true,” I wrote, “that one crucial function of the school is training people to take the jobs that society has to offer… But the much more important function of organized education is to teach the new generation that rule without which the leaders could not possibly carry on wars, ravage the country’s wealth, keep down rebels and dissenters – the rule of obedience to legal authority. And no one can do that more skillfully, more convincingly than the professional intellectual. A philosopher turned university president is best of all. If his arguments don’t work on the students – who sometimes prefer to look at the world around them than to read Kant – then he can call in the police, and after that momentary interruption (the billy club serving as exclamation point to the rational argument) the discussion can continue, in a more subdued atmosphere.”[18]

He was equally critical of the penitentiary and judicial systems:

I am convinced that imprisonment is a way of pretending to solve the problem of crime. It does nothing for the victims of crime, but perpetuates the idea of retribution, thus maintaining the endless cycle of violence in our culture. It is a cruel and useless substitute for the elimination of those conditions – poverty, unemployment, homelessness, desperation, racism, greed – which are at the root of most punished crime. The crimes of the rich and powerful go mostly unpunished…

The courtroom is one instance of the fact that while our society may be liberal and democratic in some large and vague sense, its moving parts, its smaller chambers – its classrooms, its workplaces, its corporate boardrooms, its jails, its military barracks – are flagrantly undemocratic, dominated by one commanding person or a tiny elite of power. In courtrooms judges have absolute power over the proceedings. They decide what evidence will be allowed, what witnesses will be permitted to testify, what questions can be asked.[19]

He backed up his claims convincingly in Justice in Everyday Life – The Way It Really Works (1974), in which he examined the police, courts, prisons, housing, workplaces, health care and schools, identifying systemic problems and proposing solutions on the basis of diverse testimonies.

Zinn’s views and books have long been seen by the conservative right as a serious ideological threat. Several states have attempted to ban his books from school districts, and in 2020, ten years after Zinn’s death, President Donald Trump also took aim: “Our children are instructed from propaganda tracts, like those of Howard Zinn, that try to make students ashamed of their own history.”[20]

Zinn is understandably disturbing to those who, like Trump’s 1776 Commission, seek to turn history into a mythical past under the banner of “patriotic education,” who seek to make the dominant group’s narrative exclusive in order to consolidate the power of those at the top. When the 2020 Hungarian National Curriculum sets similar targets for teaching history and literature, Howard Zinn’s point of view is much needed in Hungary.

Published in Hungarian by Tett on August 14, 2022

[1] Howard Zinn, The New Abolitionists, 1964, reprint: Haymarket Books, 2017, p. 8.

[2] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Beacon Press, 1994, 2002, p 208.

[3] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of American Empire, Metropolitan Books, 2009, p. 131.

[4] Howard Zinn, Terrorism and War, Seven Stories Press, 2002, p 28.

[5] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of American Empire, pp. 3-4.

[6] Howard Zinn, Donaldo Macedo, Howard Zinn on Democratic Education, Paradigm Publishers, 2005, p. 187.

[7] Howard Zinn, Three Plays – The Political Theater of Howard Zinn, Beacon Press, 2010, p 3.

[8] Howard Zinn, Donaldo Macedo, Howard Zinn on Democratic Education, Paradigm Publishers, 2005, p. 191.

[9] Howard Zinn and Anthony Arnove, Howard Zinn Speaks: Collected Speeches, 1963–2009, p 208.

[10] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, p 21.

[11] Howard Zinn, Donaldo Macedo, Howard Zinn on Democratic Education, Paradigm Publishers, 2005, p. 1.

[12] Howard Zinn, Disobedience and Democracy, 1968, Haymarket Books, 2013, pp 119–120.

[13] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, p x.

[14] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, p 3–4.

[15] Howard Zinn, „Governments Lie”, in A Power Governments Cannot Suppress, City Lights Books, 2007, p 199.

[16] https://www.howardzinn.org/collection/pentagon-papers-disclosure/

[17] Howard Zinn, Three Plays – The Political Theater of Howard Zinn, Beacon Press, 2010, p 14–15.

[18] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, p 186.

[19] Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, p 150–151.

[20] https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/trump-attacks-zinn-and-zep/